Hamiltonian Monte Caro

An elegant sampler that utilizes Hamiltonian dynamics to propose new states in simulations.

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (Neal, 2011) (HMC) is a popular Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm to simulate from a probability distribution and is believed to be faster than the Metropolis Hasting algorithm (Metropolis, 1953) and Langevin dynamics. However, the convergence properties are far less understood compared to its empirical successes.

In this blog, I will introduce a paper called Optimal Convergence Rate of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for Strongly Logconcave Distributions (Zongchen Chen, 2019).

Hamiltonian Dynamics

HMC algorithms conserves Hamiltonian and the volume in the phase space and enjoy the reversibility condition (by flipping a sign). It aims to simulate particles according to the laws of Hamiltonian dynamics. Consider a Hamiltonian function $\mathrm{H(x, v)}$ defined as follows

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{H(x, v)=f(x)+\|v\|^2}, \end{equation}

where $\mathrm{f}$ is the potential energy function, $\mathrm{x}$ is the position, and $\mathrm{v}$ is the velocity variable. In each step, the update of the particles $\mathrm{(x, v)}$ follows the system of (ordinary) differential equations as follows

\begin{equation}\label{hmc_eq} \mathrm{\frac{d x}{d t}=\frac{\partial H}{\partial v}=v(t) \ \ \text{and} \ \ \frac{d v}{d t}=-\frac{\partial H}{\partial x}=-\nabla f(x)}. \end{equation}

After a time interval $\mathrm{t}$, the solutions follow a ``Hamiltonian flow’’ $\mathrm{\varphi_t}$ that maps $\mathrm{(x,v)}$ to $\mathrm{(x_t(x,v), v_t(x, v))}$.

Convergence of Ideal HMC

To prove the convergence of the ideal HMC algorithms, we first assume standard assumptions.

Strong convexity We say $\mathrm{f}$ is $\mathrm{\mu}$-strongly convex if for all $\mathrm{x, y\in R^d}$, we have

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{f(y)\geq f(x)+\langle \nabla f(x), y-x\rangle + \frac{\mu}{2} \|y-x\|^2.} \end{equation}

Smoothness We also assume $\mathrm{f}$ is $\mathrm{L}$-smooth in the sense that

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{f(y)\leq f(x)+\langle \nabla f(x), y-x\rangle + \frac{L}{2} \|y-x\|^2.} \end{equation}

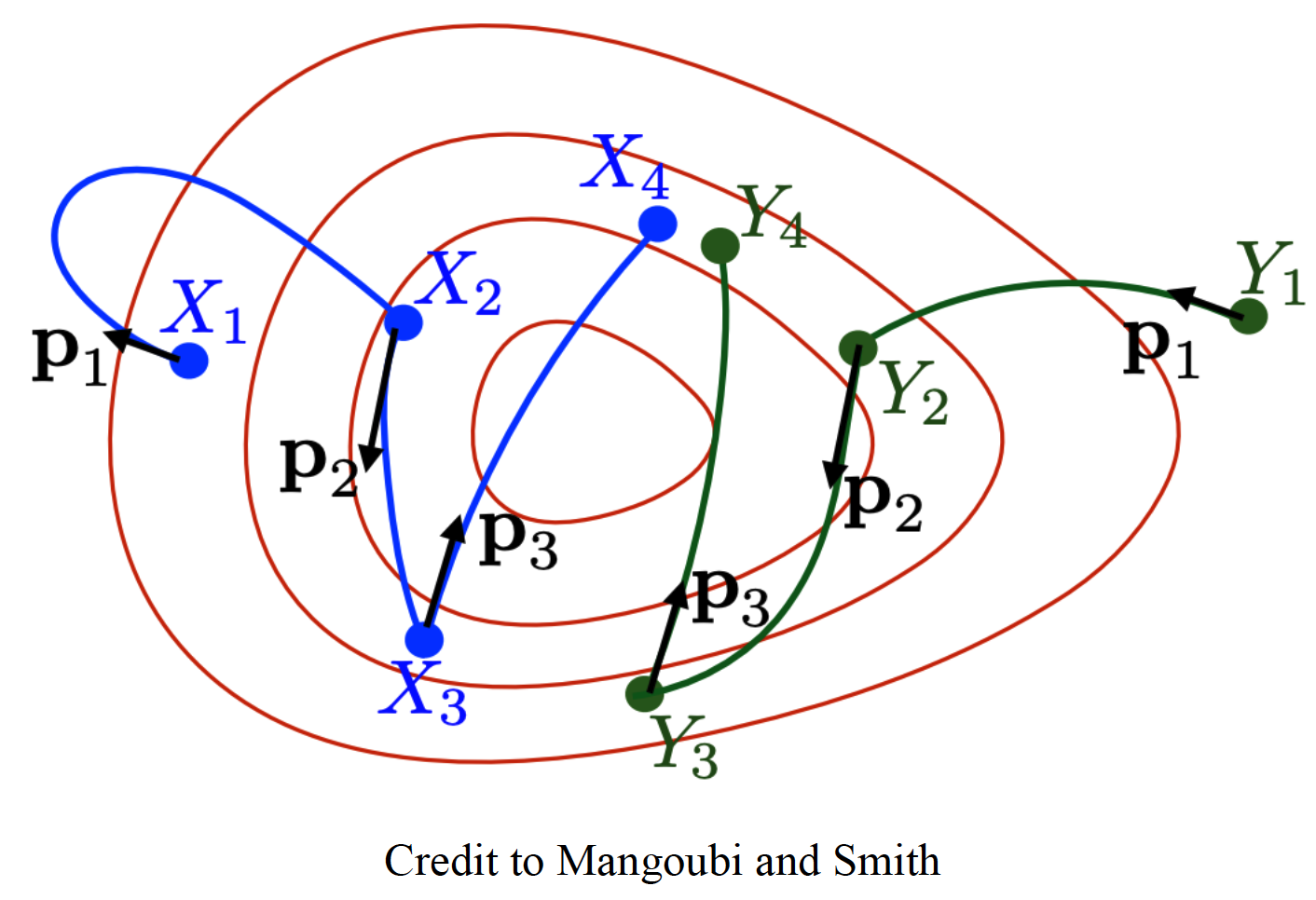

The convergence analysis hinges on the coupling of two Markov chains such that the distance between the position variables $\mathrm{x_k}$ and $\mathrm{y_k}$ (the second Markov chain) contracts in each step.

Denote by $\mathrm{x(t)}$ and $\mathrm{y(t)}$ solutions of HMC (\ref{hmc_eq}) and denote by $\mathrm{x(0)}$ and $\mathrm{y(0)}$ the initial positions of two ODEs for HMC. To faciliate the analysis of coupling techniques, we adopt the same initial velocity $\mathrm{v(0)=u(0)}$. The convergence study hinges on the contraction bound as follows

Lemma Assume the potential function $\mathrm{f}$ satisfies the convexity and smoothness assumptions. Then for $\mathrm{0\leq t \leq \frac{1}{2\sqrt{L}}}$, we have

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\|x(t)-y(t)\|^2 \leq (1-\frac{\mu}{4}t^2) \|x(0)-y(0)\|^2.} \end{equation}

Proof Consider two ODEs for HMCs:

\[\begin{align}\notag \mathrm{\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad x'(t)}&\mathrm{=v(t) \qquad\qquad \quad\text{and}\qquad y'(t)=u(t)} \notag\\\\ \qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad \mathrm{v'(t)}&\mathrm{=-\nabla f(x(t)) \quad\qquad\qquad\ \ u'(t)=-\nabla f(y(t))},\notag \end{align}\]where the initial velocities follow $\mathrm{u(0)=v(0)}$.

Taking the second derivative of $\mathrm{\frac{1}{2}\|x-y\|^2}$, we have

\[\begin{align}\notag \mathrm{\frac{d^2}{dt^2}\left(\frac{1}{2} \|x-y\|^2\right)}&\mathrm{=\frac{d}{dt}\langle v-u, x-y \rangle}\notag\\ &=\mathrm{\langle v'-u', x-y \rangle + \langle v-u, x'-y' \rangle} \notag\\ &=\mathrm{-\rho \|x-y\|^2 + \|v-u\|^2},\notag \end{align}\]where $\mathrm{\rho=\rho(t)=\frac{\langle \nabla f(x) - \nabla f(y), x-y \rangle}{\|x-y\|^2}}$.

To upper bound $\mathrm{\|v-u\|^2}$, recall that \begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\frac{d}{dt} \|x\|=\frac{d}{dx} \|x\| \cdot \frac{d}{dt} x=\frac{\langle x, \dot{x} \rangle}{\|x\|}.} \end{equation}

In what follows, we have

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\frac{d}{dt}\|v-u\|=\frac{1}{\|v-u\|}\langle v’-u’, v-u\rangle =-\frac{\langle \nabla f(x)-\nabla f(y), v-u\rangle}{\|v-u\|}.} \end{equation}

In particular for the upper bound of $\mathrm{\frac{d}{dt}\|v-u\|}$, we have

\[\begin{align} \mathrm{\left|\frac{d}{dt}\|v-u\|\right|} &\mathrm{\leq \|\nabla f(x)-\nabla f(y)\|} \notag\\ & \mathrm{\leq \sqrt{L \langle \nabla f(x) - \nabla f(y), x-y \rangle} }\notag\\ &\mathrm{ = \sqrt{L\rho \|x-y\|^2}} \notag\\ & \leq \mathrm{\sqrt{2L\rho \|x_0-y_0\|^2}}, \notag\\ \end{align}\]where the first inequality follows by Cauchy–Schwarz inequality, the second inequality follows by the L-smoothness assumption, and the last inequality follows by Claim 7 in (Zongchen Chen, 2019).

Now, we can upper bound $\mathrm{\|v-u\|^2}$ as follows

\[\begin{align} \mathrm{\|v-u\|^2} &\mathrm{\leq \left(\int_0^t \left|\frac{d}{ds}\|v-u\|\right| ds\right)^2} \notag\\ \qquad\qquad & \mathrm{\leq \left(\int_0^t \sqrt{2 L\rho} \|x_0-y_0\| ds\right)^2} \notag\\ \qquad\qquad & \mathrm{\leq 2L t \left(\int_0^t \rho ds\right) \|x_0 - y_0\|^2.} \notag\\ \end{align}\]Define the monotone increasing function

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{P=P(t)=\int_0^t \rho dt,} \end{equation}

where $\mathrm{P(0)=0}$ and $\mathrm{\mu t \leq P(t)\leq L t}$ for all $\mathrm{t\geq 0}$. Then

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{|v-u|^2 \leq 2L t P|x_0-y_0|^2.} \end{equation}

Combining the above upper bounds, we have

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\frac{d^2}{dt^2} \left(\frac{1}{2}\|x-y\|^2 \right)\leq -\rho \left(\frac{1}{2} \|x_0-y_0\|^2\right)+2Lt P \|x_0-y_0\|^2.} \end{equation}

Define $\mathrm{\alpha(t)=\frac{1}{2} \|x-y\|^2}$, then we have

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\alpha’(t)\leq -\alpha(0) (\rho(t)-4L t P(t)).} \end{equation}

Integrating both sides and combining the fact that $\alpha’(0)=0$, we have

\[\begin{align} \mathrm{\alpha'(t)}&\mathrm{=\int_0^t \alpha'(s) ds} \notag\\ \qquad\ &\mathrm{\leq -\int_0^t \alpha(0) (\rho(s)-4L t P(s))ds} \notag\\ \qquad\ &\mathrm{\leq -\alpha(t)\left(P(t) - 4LP(t) \int_0^t s ds\right)} \notag\\ \qquad\ &\mathrm{=-\alpha(0)P(t)(1-2Lt^2).} \notag \end{align}\]Choose $\mathrm{t \in [0, \frac{1}{2\sqrt{L}}]}$, then we can deduce that \begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\alpha’(t)\leq -\alpha(0) \frac{\mu}{2} t.} \end{equation}

Eventually, we have the desired result such that

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\alpha(t)=\alpha(0)+\int_0^t \alpha’(s) d s \leq \alpha(0) \left(1-\frac{\mu}{4} t^2\right).} \end{equation}

Setting $\mathrm{t=T=1/(c\sqrt{L})}$ for some constant $\mathrm{c\geq 2}$, we get

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{|x(T)-y(T)|^2 \leq \left(1-\frac{1}{4c^2 \kappa}\right)|x(0)-y(0)|^2.} \end{equation}

Eventually, we can achieve the convergence in Wasserstein distance such that

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{W^2_2(\nu_k, \pi)\leq E\left[|x_k-y_k|^2\right]\leq \left(1-\frac{1}{4c^2 \kappa}\right)^k O(1).} \end{equation}

Discretized HMC

(Mangoubi & Vishnoi, 2018) proposed to approximate the Hamiltonian trajectory with a second-order Euler integrator such that

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\hat{x_{\eta}}(x, v)=x+v \eta - \frac{1}{2} \nabla f(x), \quad \hat{v_{\eta}}(x, v)=v-\eta \nabla f(x) - \frac{1}{2} \eta^2 \nabla^2 f(x) v.} \end{equation}

Since Hessian is expensive to computate and store, an approximation is conducted through

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\nabla^2 f(x) v \approx \frac{\nabla f(\hat{x_{\eta}}) - \nabla f(x)}{\eta},} \end{equation}

Now, the numerical integrator follows that

\begin{equation}\notag \mathrm{\hat{x_{\eta}}(x, v)=x+v \eta - \frac{1}{2} \nabla f(x), \qquad \hat{v_{\eta}}(x, v)=v-\frac{1}{2}\eta (\nabla f(x) - \nabla f(\hat{x_{\eta}})).} \end{equation}

It can be shown that such a discretized HMC requires O($\mathrm{d^{\frac{1}{4}} \epsilon^{-\frac{1}{2}}}$) gradient evaluations under proper regularity assumptions (Mangoubi & Vishnoi, 2018). Other interesting persepectives can be seen in (“Fast Mixing of Metropolized Hamiltonian Monte Carlo: Benefits of Multi-Step Gradients,” 2020).

Conclusions

Properly tuning the number of leapfrog steps is important for maximizing the contraction to accelerate convergence. From the perspective of methodology, the no-U-turn sampler proposes to automatically adjust the number of leapfrog steps and potentially exploits this idea by checking the inner product of postion and velocity (Hoffman, 2014).

- Neal, R. M. (2011). MCMC using Hamiltonian dynamics. Handbook of Markov Chain Monte Carlo.

- Metropolis, et al. (1953). Equation of State Calculations by Fast Computing Machines. Journal of Chemical Physics.

- Zongchen Chen, S. S. V. (2019). Optimal Convergence Rate of Hamiltonian Monte Carlo for Strongly Logconcave Distributions. Approximation, Randomization, and Combinatorial Optimization. Algorithms and Techniques.

- Mangoubi, O., & Vishnoi, N. K. (2018). Dimensionally tight running time bounds for second-order Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. NeurIPS.

- Fast mixing of Metropolized Hamiltonian Monte Carlo: Benefits of multi-step gradients. (2020). Journal of Machine Learning Research.

- Hoffman, M. D. (2014). The No-U-Turn Sampler: Adaptively Setting Path Lengths in Hamiltonian Monte Carlo. Journal of Machine Learning Research.